By Jonathan Goodman

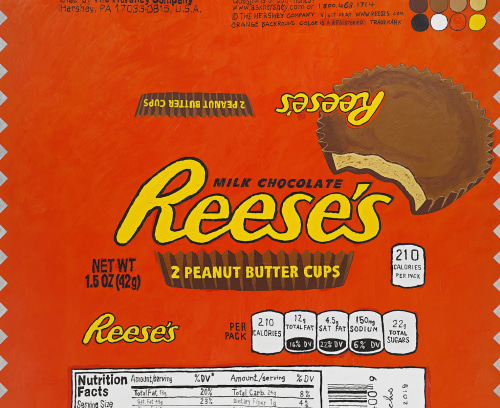

Tom Sachs, in a mid-career show—his first at Acquavella Galleries—is offering “handmade paintings” aligned with classic American, mostly commercial iconography: a reproduction of the Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup wrapper, the McDonald's Golden Arches, an American flag. These images are so ubiquitous as to have taken on definitive status, giving them an authority nearly ethical in their quality; all this despite the fact that Sachs’s paintings are mostly of logos of things to be sold. Indeed, in the introductory materials online, a quote by Sachs is prominently displayed: “There is power in logos and there is power in good advertising.” No doubt this is true, but it can be debated whether the imagery of advertising can be effectively read as examples of art, in large part because we cannot separate the American business perspective from the visual appeal of the candy wrapper.

But maybe that’s the point: ever since Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) and Green Coca-Cola Bottles (1962), there has been a strong drive toward an apotheosis of merchandise, not least in part because the materiality/product design of the objects Warhol and Sachs reproduce in their artworks is so seductive in the first place. At the same time, when well-respected artists turn their attention to the commercial, they extend their imprimatur to a stance that many artists might reject. Thus, the strength—but also the trouble—with a show like this depends entirely on whether we accept or reject the attractiveness of merchandising—as visual presentation and thematic idolatry. There is little doubt Sachs agrees with Warhol’s imagistic projection of American materialism. In art, we can find no greater support for our way of life than to include the flag, whose innate patriotism has been the subject even of artwork critical of the American way.

As odd as it may seem, McDonald’s (2020) celebrates the American corporate food industry, although this is undercut in the show by Krusty O’s (2019), a painting of Krusty the Clown from The Simpsons, a subversive icon like no other on the cover of a flattened cereal box. The fast-food giant is established to the point of cliché, and in response, Sachs has painted a handmade version of its logo. The human awkwardness of such mimicry might be considered a challenge to the huge hamburger purveyor, even as it underscores how impossible it is to escape advertising today. Indeed, Sachs’s very choice of McDonald’s as a theme for a painting, complete with the immediately recognizable Golden Arches stretching across it, can easily be seen as a critique just as much as an approval of our informal, industrial relationship to food production and consumption. So, the painting’s handmade, imprecise quality, easily evident, undercuts the impersonal sameness of the food—if one traveled across America, eating only at McDonald’s, it would seem as if the trip had never gone anywhere! Sachs opposes the sameness of our lives by including the small eccentricities of the hand. The image, like the show, is not an elegy but rather an ode to a way of life that seems permanently written into our existence. On the lower left-hand side of the painting, Sachs includes a small American flag, and beneath it, his signature; it is his own logo, writ small beneath a larger one.

Reese’s (2019) is an exquisite copy of the candy wrapper, complete with jagged edges, several reiterations of the logo, and the white box detailing calories, nutrients, etc. This must be a work of love, and indeed, it is hard not to enjoy the salty/sweet confection. The surface of Reese’s is enriched by the use of palladium; in another work, gold leaf is employed. These elegant substances elevate the quotidian status of the paintings’ subjects, even should we be unaware of their presence when we look at Sachs’s art. In doing so, the artist asserts a visual value that supports the meaningfulness and even the economic weight of an imagery easily regarded as common. There is power in logos, and investing them with materials associated with expensive taste lifts the imagery to a place of considerable elegance. As a result, the artificial grace of Sachs’s challenging show is also a critique of the relentless uniformity troubling the culture at large. He has chosen to plumb a tradition celebrating the appeal of advertising, offering to his viewers a demotic sublime.